I do not think Orkney could have had a better summer even if we had asked for it.

Now it is August, when in the old days, with the nights drawing in noticeably, we would be thinking of ‘hairst’, but for most of us those days are far away.

In this letter I’m planning something completely different, but before getting under way I will briefly refer to our latest doings.

Almost all of the usual summer’s work is complete and one day, earlier in the summer, the Memorial Hall got tarred, and on Friday, August 15, the association planned a light-hearted golf tournament, slide show and dance which was held in the Memorial Hall.

North Ronaldsay actually boasts a nine hole golf course first created by the laird of the island, William H. Traill and his brother John in the late 1890s.

A reasonable turnout made their way round the course. Many were playing their first game of golf while others participated with varying handicaps. Later, the slide show and dance got under way.

Rosemary Robertson, introduced by Peter Donnelly, proceeded to show some magnificent slides taken recently over an extensive area in the Indian province of Gujarat.

The colours depicted – dress, jewellery, markets, architecture and so on – as might be expected, were quite stunning, and as one of the audience remarked, the photographs were, in many instances, superior to work seen in the National Geographic magazine.

After tea, shortbread etc a lively dance got under way. A large number of visitors were present and although dance steps were often somewhat unorthodox at times, the dance was a great success.

Peter Donnelly presented the North Ronaldsay golf trophy to John Price (a visitor) during a welcome pause – it remains on the island with the winner’s name engraved on a little plate.

Three accordions provided toe-tapping music. Musicians were Lottie, Ann, and Roddy Watt. Roddy, a visitor from the south, was back on the island after a few years of absence renewing his musical collaboration with our two local players. Around two in the morning this rather splendid evening came to a close.

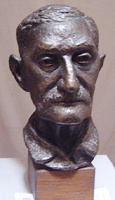

Well, in my last letter to The Orcadian, part of a portrait of my grandmother was seen. This time I would like to include the full portrait – a three-quarter study. In addition, I also include three other portraits.

You see I thought it would be interesting to do a little piece called Island Portraits, or some such title, along with a brief ‘portrait’ in words – so to speak – of each islander.

The portraits, by the way, are firstly modelled in clay. Then a two piece plaster of Paris mould is taken from each sculpture.

Those moulds are filled with plaster, though not as solid casts – a laminate in other words.

The mould is then chipped away, leaving an exact plaster copy of the original clay model.

Plaster is at least much more enduring than clay, but nevertheless fragile. Of course, the ideal copy would be bronze, but for that presentation we are talking about some £500 to £600 for a head-only portrait.

In my last letter I told you a little about my grandmother – her golden wedding and her almost epic trip to Chicago in 1895 to bring back a child whose mother had died.

My grandmother, Catherine, was 95 when she died in 1965. She and her husband, William Tulloch, Cruesbreck, brought up a family of six.

Those were the early days of the 20th century when North Ronaldsay’s population would have been well over 400, when horses or oxen were used for much of the land work: ploughing, cultivating, pulling, firstly reapers then binders, bringing in the stacks of corn and oats, carting ‘ware’ (seaweed) as an organic fertiliser, transporting turnips, stones for dykes and houses, flag stones for roofs; driving the early mills for thrashing the seed for the land and for the making of meal – bere and oat meal.

The meal was ground at a watermill and a windmill and eventually by an engine-powered mill.

Then there was the killing of a pig with its pork shared with neighbours; fish from the sea; mutton from the native sheep; cows to milk – cheese and butter made; wool to spin for blankets, underwear, gloves and stockings. During those times there was no piped water, no water closets, no electricity, no cars, planes, or outboard motors for the fishing, no interior heating, no television or for that matter radio, until I suppose the early 30s – a way of life very far removed from today’s relatively easy existence.

My grandmother was a great knitter and she and a sister, when they were young, evolved a knitting pattern which featured the letters of the alphabet, woven, in bright contrasting colours.

They also knitted an X and 0 design as well as the Fair Isle patterns. This work was sold in Kirkwall for a time.

Towards the end of her long life she continued to knit the alphabet stockings with, as I remember, the Member of Parliament for Orkney and Shetland, Jo Grimond, commissioning a pair. All of this gives a flavour of Catherine’s life and that of her contemporaries of those days and times.

My next portrait is Bethia Fotheringhame, who happens to be the young child brought back from Chicago by my grandmother.

My grandfather would have been her uncle and she was brought up at his farm of Cruesbreck. She left the island in 1910 to attend the grammar school in Kirkwall coming back for holidays only at the end of each term. Bethia went on to train as a teacher, teaching, firstly in Wyre and subsequently in Sanday where she married Charles Fotheringhame from Templehall in 1930.

Their daughter, Mary Anne, is my very knowledgeable informant from Sanday that I have mentioned from time-to-time. She further tells me (when checking dates) that one of her parents’ wedding presents was a wireless (a Mullard) which was operated with two batteries – one dry and the other a lead acid battery.

After her marriage Bethia gave up teaching and became a farmer’s wife. She was, for many years, a church organist in Sanday.

Numerous North Ronaldsay folk on their way to the island on holiday by mail-boat as they sailed across the ‘Firt’ (the Firth between Sanday and North Ronaldsay) received homely accommodation at Templehall – sometimes for days (as I remember well in my time) when the weather was bad.

She continued to often come back for holidays and to help at the old home. Bethia had an excellent memory and, therefore, a great knowledge of the island and in particular of kindred – relationships was always a great topic of conversation indulged in with much interest by many islanders of that time. It was on one of those many visits that I had her sit for her portrait.

The third portrait is of Alec Swanney, of Sangar, modelled not long before he died in 1967, when he was 91.

Alec was a real character and left in the early 1900s to farm in the Canadian prairie.

A number of islanders went to that country, others chose to try their luck mainly in the USA or Australia.

In Canada, in the wintertime, conditions in some areas could be severe, with temperatures dropping as low as 51 degrees below zero with snow sometimes as high as telegraph poles.

Imagine the hardship of those old pioneering homesteaders living without proper heating in such conditions. Water left overnight in a pail, for example, in their wood shacks would have ice at least half an inch thick on top in the morning.

In fact, Alec lost a toe through frostbite with also some damage, it is said, to the points of his fingers.

Certainly those early wheat farmers, living some 50 miles south east of Moosejaw, Saskatchewan, working with horse and oxen, harvesting the wheat and so on, had a hard life initially.

Alec worked a ‘quarter’ section which I am told amounted to 160 acres. The wheat had to be hauled by wagon, or on sleigh in the wintertime to a town some 25 miles distant – a day’s haul to get there and another to get back home.

Most of this information I have read in an account of those early days written by an uncle of mine, Hughie, who also went to Canada as a young man in the late 1920s.

He writes at length, mentioning the dangers of falling asleep outside in those extreme temperatures; of dust storms, grasshoppers, army worms, no money in the Hungry Thirties, evictions, foreclosures and so on.

Shortly after Alec’s brother died in 1934 he returned to the island to work, along with his sister Bella, the home croft of Sangar.

Ox and pony was his power source. I wonder what he thought of a neighbour, such as myself, modelling his likeness in clay?

My fourth portrait is that of Annie Thomson of Bewan. She was born in 1881 and died in 1965.

Her portrait, as were the other three, was modelled in the early 1960s and not long before she died. Annie had a great reputation as a storyteller. She also had command of an extensive store of old Orkney words.

In the late 1950s, Professor Jim Mather, who carried out research work for the Linguistic Survey, Edinburgh, made recordings capturing her dialect and as many of the old words as possible.

Those words are relics of the older language of Orkney – the Orkney Norn – a dialect of Norwegian.

Bewan, to which Annie moved on marrying, is not far from the sea and at one of the main sheep punding areas.

Many a cup of tea was given to those folk busy in the spring, bringing the native sheep in by for lambing or at the summer clipping punds – a pund is a stone built sheep trap.

Annie, apart from her household chores, was not frightened to tackle any type of men’s work and often would be at sea with her husband Hughie fishing for crab and lobster.

In those days of the early 1960s I would frequently stop past Bewan for a cup o’ tea as I passed by, maybe on a painting expedition.

Annie’s stories were great entertainment and I regret my inability to retain them in much degree as I do other exchanges with islanders of around that generation.

Well, I have come almost to the end of my letter. A closing paragraph came to mind when I was out cutting weeds again – it happened that I retraced old paths and relived past times.

The day had been exceptionally warm and even in the late evening it was hot work wielding a scythe.

I took a sudden whim, threw my scythe and honing stone aside, and set off along the ‘west banks’ to the north to visit the ‘Gray Stane Pow’ – a natural and smallish bathing pool five feet or so deep at its deepest.

Being situated relatively far down among the rocks, during high tides, with sea motion on, it gets a clean out from time to time.

In the 1960s we, my two sisters and two younger brothers, were down at this pool many a day and many a summer’s evening.

Into its darkening waters I plunged and swam a few lengths in water as warm as I knew it would be. That was fun as the years flew away.

A little later, while taking an easier inland route on my way home, an almost full, orange coloured moon was rising just above Nether Linnay. The scene, though quite beautiful, was sad since this house now stands dark and empty.

Briefly, I stood at the door through which frequently in the past I had entered its lightsome interior.

As I continued on my way home, the moon, gaining height, threw an almost golden path across the East Sea. Then I passed by Burray, another lightsome house, and so on past Longar, and Ancum with its memories, and then Sangar. Although this is now a new house incorporating the original building I could see in my mind’s eye the old farmhouse as it used to be. Almost 40 years ago I had spent a number of evenings working on Alec’s portrait. There he would sit, with his sister Bella most likely seated close by the fire knitting. Above, and a little in front of his head was a Tilley lamp, its light diffused by an opaque polythene screen which I had constructed to ensure an effect as near to a natural top light as possible.

It’s strange to cast one’s mind back to those times, and I wonder if Alec, as he sat for me, was dreaming of his days as a youthful homesteader on the far away and wild Canadian prairie.