A postcard from Bantry prompts reminder of Orkney new year of 1918

Tonight, March 19, I am, as they say, “putting pen to paper”, or rather, to be more accurate, tapping the computer keys. It has been such a perfect day with spring definitely in the air that the thought came to mind that I might try a “voar” letter.

This morning was warm and calm with hardly a cloud in the sky – the sort of morning that tempts one to take the day off. With that lazy idea in mind I thought to myself: “To heck with all the undone jobs, I’m simply going to go visiting”.

So, having got myself into a “boony” (tidied up), away I set on foot along the northyard road to make a call that I had been planning for a while.

As I travelled along, skylarks were singing, and Ancum loch sparkled in the morning sun. In fact the air was full of the sounds of spring: Whaups, Sheldros, and Haedycraas were calling from all directions and, here and there, the “millennium daffodils” – as I call them since the planting of those flowers, and others, along the roadways was a millennium idea – were beginning to come into bloom.

As yet the lurking weeds are lying low and the surrounding fields appear generally tidy, and, with the prolonged spell of fine weather that we have been enjoying, the island is looking pretty good for the time of year.

Before very long carpets of undesirable dandelions will transform great areas of the island into a blaze of colour. The change in farming methods over the last couple of decades has allowed the ever-increasing encroachment of such weeds as the dandelion and the dochan. How all this will finally turn out is indeed a question – since I cannot see the old traditional system of rotation farming ever coming back.

Along the public road one comes to a point where a fairly prominent man-made ridge of ground has been cut through, to allow for the construction of the thoroughfare. This is actually the remains of what Hugh Marwick (1881-1965) the Orkney historian and linguistic scholar, described as a “treb dyke” – known locally as Matches dyke. It crosses the island from west to east. And further south there is the remains of another treb dyke, known as the Muckle Gersty.

Those two prehistoric earthen dykes divide the island into three fairly equal portions. Legend has it that at one time North Ronaldsay belonged to three brothers, but whatever the truth of the mysterious dykes their construction must have entailed a considerable amount of physical work. I suppose originally they could have been in the teens of feet high.

Their total length is a little over two miles. Even with today’s machinery such a construction would be a formidable achievement. It is still possible to see much of their remains and on this spring day I stopped for a minute or two to think about those early inhabitants. Who were they and how did they manage to live on the island? What would have been their thoughts all those thousands of years ago as they stood where I was standing? I suppose they were not looking back or speculating about past times, as I was, since they probably were the makers of the island’s earliest history. No doubt, though, like myself, they surely would have heard, and enjoyed the song of the skylark.

Talking about history, it’s amazing how within a short period of time photographs become part of history and how, when trying to name individuals in a photograph, some folks’ looks change more than others. Take school photographs for instance. When in the house of my planned visit and enjoying a “cuppa” we were looking at two island school photographs, one taken, I think, in the early thirties – eight years or so before I was born.

I thought I could recognise one or two individuals – there was a definite likeness, and with others I could see a likeness when I was told who was who. School photographs capture generations and if we know the names of the pupils in the classes recorded then each person has a history to investigate. Did they leave North Ronaldsay or stay? What did they do with their lives? Did they marry? Did they have a family and if so what happened to the family?

Take other categories such as views of the island, of houses, of croft and sea work, community events, the war years, shipping and the air service and so on. Such snapshots in time — some dating back as far as the late1800s — can tell the history of an island. It will involve committed researchers in many investigations and interviews. Most likely the register of births, marriages and deaths will be looked at, as will public archives, newspapers, and all sorts of documents here and there, and near and far.

With my visit at an end I retraced my footsteps south in sunlight of almost summer warmth and intensity. It was litesome to hear the birds calling once again and to stroll along absorbing the sounds and smells of the island. As I walked homewards I picked a flowering sprig of Winnie’s veronica, small bushes of which decorate the roadside. This evergreen reminds me of the harvest home as we use them for wall display — they have an elegant scent all of their own. In the west, over 100 calling geese were cutting across the sky in two vee formations that kept changing shape and direction. I wonder what they are thinking of – could it be that they are they toying with the idea of living in Orkney?

Later in the evening I myself had a visitor and we were looking over photographs, and one or two old postcards. Postcards, by the way, are often very interesting, for there the writers have left their thoughts and brief news of the moment. The photos at this house, which are actually made up of three houses’ collections, amount easily to a thousand or more – one night I made an initial count of them. They have somehow to be categorised and researched. And then there are all the island’s photographs, and the photographs of other North Ronaldsay folk scattered across the world to investigate.

Anyhow, one postcard in particular, dating back to 1917, took our fancy. It, as will be seen, along with two other photographs, well illustrates the points I have just been making.

At that time World War One was still being bitterly fought. Today, some 86 years later, we are involved in a much more controversial and vastly different war. One great difference between recent wars and World War One was the duration timescale, and I am always amazed that countries could continue fighting for so many years.

Apparently, in 1918, the conflict was costing Britain £7 million a day (there appears to be, on so many occasions, plenty of money for killing people but none for sorting out all our problems). In the constant horrific battles of that war thousands of men could die in a morning.

At Passchendaele (July 31-November 10, 1917), for instance, British casualties alone were at least 300,000, and by the end of hostilities the British Empire would have lost almost onemillion combatants. Just suppose for a moment that we could have followed the action from day to day on TV as we do with the war in Iraq.

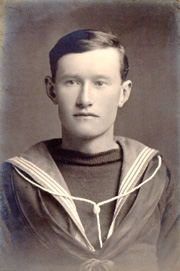

But to get back to our postcard story. Among the many photographs of World War One servicemen at Antabreck, there are a number of John Tulloch from Upper Linnay. There is also, interestingly, a small photograph of the boat on which he served. The boat (Canadian built) was the forerunner of the British MTB of World War Two. They were 80 feet long, top speed 19 knots, armed with a three-pounder gun, and were used for anti-submarine work, minelaying and inshore minesweeping. They formed part of the Auxiliary Patrol which was mainly manned by RNVR personnel. (inf. Imperial War Museum) On the bow of the motor launch it’s possible to read the boat’s identification number, ML 173.

The post card is actually a New Year card, illustrated with silver bells, ribbons and posies of violets, with the words “A Glad New Year to You”. In the centre of the card there is a painting of a rustic scene by a river. The card has a halfpenny stamp depicting the head of King George V.

It is addressed to Miss J. Tulloch, Queens Nurse, Schoolhouse, Orphir, Orkney, Scotland.

John Tulloch writes the date, December 18, 1917, and below the date he notes HMML 173, c/o GPO London. The postmark is Bantry, County Cork, southern Ireland, from where the ML worked.

The message reads: “ Dear Aunt, Just a PC to let you know that I have got back safely. I did not manage to see Helen as I passed through Edinburgh. How did you manage to get home that night I saw you in Kirkwall. I had a letter from Helen today. She has seen Willie of Cruesbreck in Edinburgh. She had a letter from our Willie short ago. He is keeping well. I will stop now — wishing you a Happy New Year. From John”.

John Tulloch, from Upper Linnay, North Ronaldsay, survived World War One to return to his island home.

John must have been home in North Ronaldsay on leave. Helen was John’s sister and worked in Edinburgh in service for a time. In December, 1917, there was heavy snow in Orkney which could explain the question about getting back to Orphir.

John Tulloch, from Upper Linnay, North Ronaldsay, survived World War One to return to his island home.

Willie of Cruesbreck was my uncle (he served on minesweeping trawlers: Leith, Edinburgh, would have been his base).

The other Willie referred to is most likely John’s brother who served in the Seaforth Highlanders and who was shot by a German sniper in 1918 at the very end of the war.

There is a simple little verse on the post card:-

‘Take this loving wish from me:

Joyful may the New Year be:

May its days be free from trouble,

And all the joys of life be double.’

John Tulloch was mentioned in dispatches. He returned to North Ronaldsay, married, brought up a family, and lived his life on the island.